The Automotive Prints in James Bond's flat in Dr. No

It's rare that we get a glimpse in Bond's own apartment, but when we do, we look for the items that we can use in our own home. In this article, we focus on the automotive print wall art seen in James Bond's flat in the first 007 film, Dr. No.

Guest author: George Smiley

February 2025

Through the early years of the Bond series, each successive Bond was bigger than the last one, resulting from ever-increasing budgets based on the box office performance of each film. By 1967 and the production of “You Only Live Twice,” just the set for the infamous hollow volcano reportedly cost $1.1 million, or in other words, more than the entire budget of Dr. No, just five years earlier.

Watching Dr. No, the reality that it’s a smaller film than YOLT, TB, or even FRWL, is clearly apparent. But it never looks like a cheap film. Ken Adams’ unmistakable style is evident throughout, but it is in the unappreciated art of Set Dressing where Adams’ vision is populated with furniture and various objet d'art, giving the sets a personality of their own. Much of the credit for this lies with Set Dresser Freda Pearson, and Dressing Props man Dickie Bamber. Their ability to fill a set interestingly but on the cheap is apparent throughout. M’s iconic office had paintings on the wall that were literally framed pieces of cardboard, and the padded door was a vinyl fabric often referred to as “leatherette.” Miss Taro’s apartment is the same set used for the lobby of Bond’s Kingston Hotel, with some creative rearrangement and new set dressing.

One of the more intriguing sets, because it is so evocative of the novels and yet so bland in its appearance, is Bond’s flat, seen briefly early in the film.

The cinematic portrayal of Bond’s residence has always been a rarity - and the place has never looked the same twice. Conversely, Fleming frequently placed Bond in his flat, describing it in several novels, including Moonraker, Thunderball, and Diamonds Are Forever.

Cinematically, Live And Let Die is a glaring shout-out to the styles of the 1970s, while SPECTRE provides a window into Bond’s psyche, with the flat practically screaming, “…all this is temporary…,” tying in almost painfully with the fatalistic outlook of the Daniel Craig interpretation.

But for Connery, his Bond gets an apartment that, while more or less faithful to the generalities of Fleming’s descriptions, appears to have a generic, “one-size-fits-all” appearance. Indeed, the set would not have been out of place on an episode of “The Avengers” or “The Saint.”

Although he may very well have been involved, one at least hopes that the somewhat pedestrian design of Bond’s gaff had nothing to do with the great Ken Adam. I like to think that it was a pre-existing set at Pinewood, perfect for a day of filming a few quick set-ups to bridge the London sequences with Bond’s arrival in Jamaica and the commencement of the story proper.

Nevertheless, one could argue that despite itself, the set works, and to a large degree, it’s because of the set dressing. For me, evidence of this is the fact that there has always been one bit of set dressing in Dr. No that fascinated me, and it was in Bond’s bedroom. Specifically, a bit of wall art. Bond aficionados (and if you’re reading this, I’m guessing you are one) will likely already have a rather good idea of what wall art I’m referring to. Bond crashes into the bedroom, his new PPK at the ready, to confront the “intruder,” finding instead Sylvia Trench, clad only in heels, one of Bond’s pajama shirts, and a putter. To the left of the door, on the wall above the television, there is a set of five prints depicting antique cars.

They’re in shot for most of the scene and have always caught my eye. They just work for some reason, seeming to be exactly the sort of thing that one might have found in a gentleman's bachelor flat in the early 1960s. After literal decades of idle curiosity as to the specifics of the cars and the origin of the prints, I recently re-watched Dr. No and became determined that, with the power of the internet, I would track down these elusive bits of Bond ephemera.

Actually, it didn’t take exceptionally long.

I was surprised to find a general lack of discussion about them online. The one specific mention I found was an article breaking down the props and furnishings of Bond’s cinematic apartments, in which the prints were named as generic prints of antique cars, and that one could likely find similar ones on eBay or Etsy.

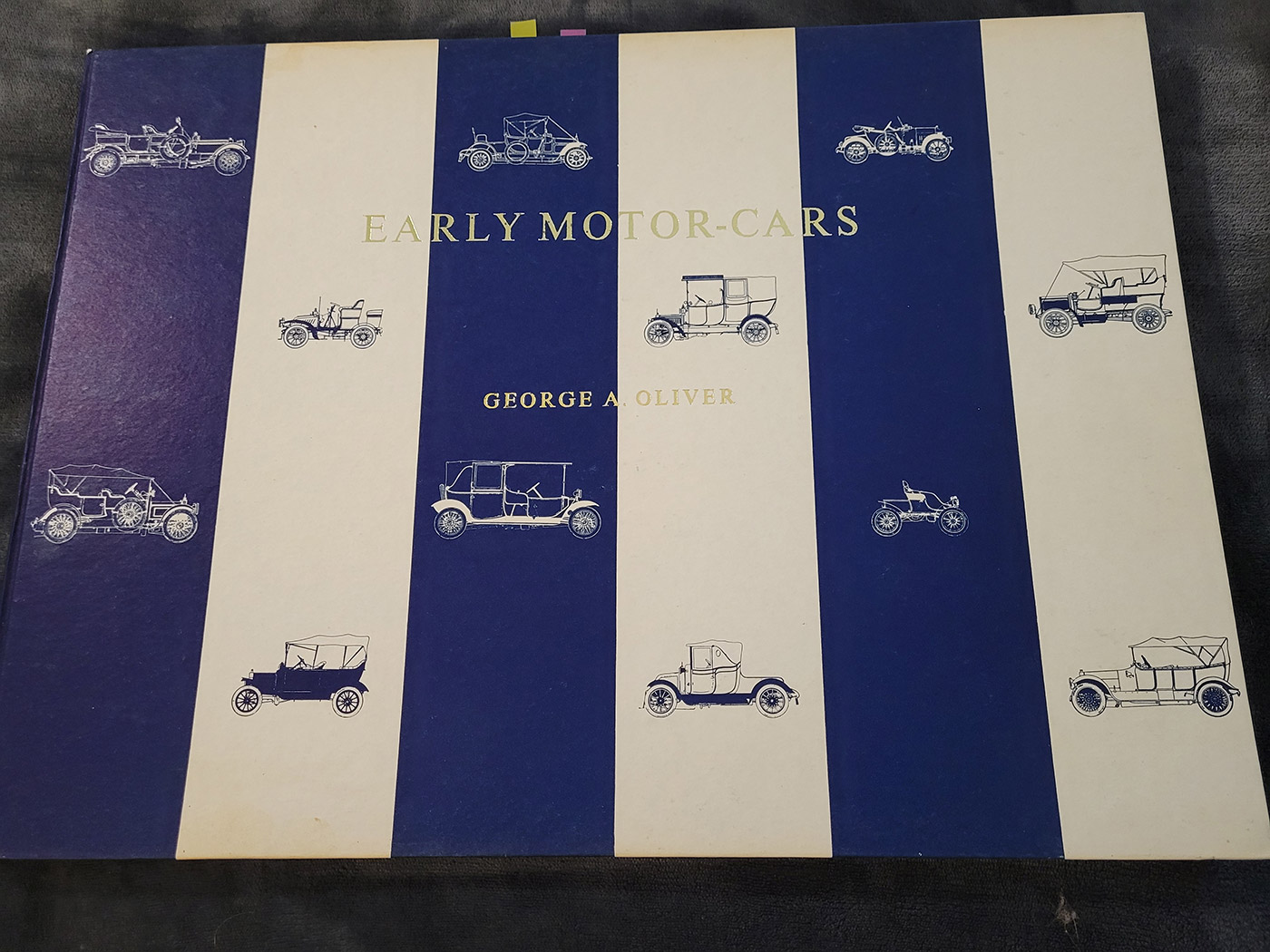

Casting the net a bit wider, I searched for automotive illustrators of the 1950s and immediately struck pay dirt. I found a book titled Early Motor Cars, 1905 – 1915, by an illustrator called George A. Oliver, who specialized in drawing classic automobiles and whose work appeared frequently in magazines of the era.

The George A. Oliver automotive illustrations might have been available as individual prints. There are currently a handful of vintage prints online (find the book and prints on eBay), but there are so few that it’s difficult to be sure if all the car prints were available. Another possibility is that the ‘prints’ in Bond’s apartment were actually pages from taken from the “Early Motor Cars, 1905 – 1915” book.

I found a copy of the book for sale in particularly good condition for a fraction of what other copies were going for and quickly identified the five cars appearing on 007’s wall.

1 - 1913 Morris 'Oxford' 9hp two-seater

2 - 1904 De Dion Bouton 8hp

3 - 1904 Oldsmobile 7 Curved Dash

4 - 1915 Ford Model “T” four-seat Tourer

5 - 1911 Adler 12

So now I had the book, I knew the cars depicted. But this created in my mind another puzzle- why in the hell were these specific cars chosen? They’re not exactly what one might have expected James Bond to decorate his bedroom with, especially considering some of the other cars in the book that didn’t make it onto the wall, including a Daimler and a Rolls-Royce.

But this is when my wife’s knowledge of interior decorating stepped in - designers commonly use “the rule of three.” This states that grouping items in odd numbers is more visually appealing and creates a more balanced and inviting space compared to even numbers.

It would seem that Freda Pearson chose five pages to frame and fill the wall space, creating an interesting contrast of three on top and two on the bottom. That arrangement should have felt top-heavy; but by using two larger prints for the bottom, it was balanced out. But Freda and Dickie were still working with a limited amount of wall space, so the two larger prints had to be bigger, but not too much bigger.

Another consideration was the colors of the cars and how those colors would work with the color of the wall itself. Taking the basic guidelines of size and color into consideration, the five Freda selected out of the book were almost the only ones that could have worked.

Other cars in the book were too large (as with the aforementioned Rolls) or were the right size but the wrong color (in fact, one option would have been almost identical in color to Bond’s green walls).

So, why these five cars? Simple - they were the ones that worked best in the space. In a real-world situation, this would be the equivalent of one’s interior decorator placing something in the décor for no other reason than it brought the room together. Whether the client cared for it or not, or would have ever bought it for themselves, was immaterial. Giving a decorator a free hand implies either great trust or an equally great level of indifference, and interestingly, this is just the sort of indifference the literary Bond would have displayed toward the décor of his flat.

He may be, as he described it, “old maidish” about certain things - the kind of coffee pot to use, or how long to cook a perfect boiled egg, but for wall hangings, one can practically hear him cut through his Scottish housekeeper’s questions on what to tell the decorators the next day and simply admonish her, “For heaven’s sake, May! Just tell them to put some rubbish on the walls to make everything respectable looking! It’s not the bloody Savoy!”